Written by Dominique Engome Tchupo, Ph.D.

Senior Human Factors Researcher

Jumpseat Research

The terms User Experience (UX) and Human Factors (HF) are sometimes used interchangeably. While these two are related but different disciplines, it’s often hard to understand where one starts and the other ends. This is especially true when looking at job descriptions for both HF and UX roles, as they tend to be very similar down to the requirements.

So, what exactly are Human Factors and UX?

UX is a discipline concerned with understanding what users want and need and using those insights in the product design process. UX encompasses everything surrounding users’ interactions with a product, with the goal of making things both usable and pleasant to use. Although Don Norman coined the term User Experience in 1993, UX was practiced as far back as the 1940s. The UX field experienced a large boom in the 1980s, with things like Apple Computer’s release of the original Macintosh in 1984. This was the first mass-market personal computer with a graphical user interface, built-in screen, and a mouse. This release established Apple as a leader in UX. Heard less often outside of specialized circles is the term Human Factors research or engineering. The study of Human Factors, specifically with regards to performance, has a very long history. It can be traced back to the late 1890s with Frederick W. Taylor modifying the way workers performed their tasks by providing them with customized tools. In the 1900s, psychology was added to the study of human performance which further grew the discipline. However, the interest in Human Factors really came into sharp focus during World War II, when the military started sponsoring most of the HF work happening. After the war, the private sector started doing more HF research, with companies like Boeing creating their own HF teams, and Bell Laboratories having an HF group that advised their engineers.

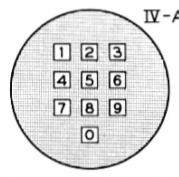

As stated by Jakob Neilson, it is hard to draw the line between traditional Human Factors and User Experience, however one early example of UX breaking off from traditional HF is at Bell Laboratories, with the design of the touchtone keypad. The touchtone keypad is what replaced the rotary dial, allowing you to press a button on the keypad which emits a dial tone. Bell Labs tested many layouts for the organization of the numbers on the keypad and ultimately decided on this one (see Figure 1), and the fact that it is still used today shows how well it was designed. The principles that guided this well-received design, such as feedback (the tone when you press a button), are now well-known, formalized UX principles used across industries and devices today.

Figure 1: Final Touchtone Keypad Design

What is Human Factors Research?

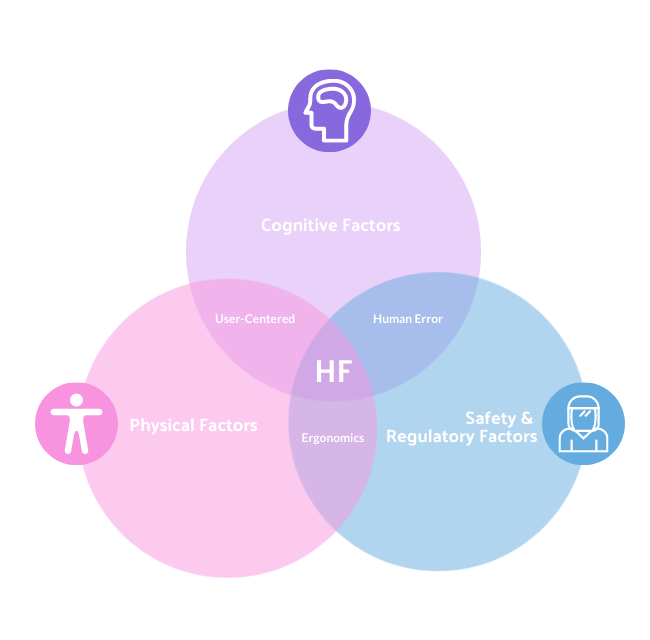

Human Factors research goes by many names, Human Factors Psychology, Human Factors Engineering, and Engineering Psychology. All of these terms refer to the study of human abilities, limitations, behaviors, and processes, both cognitive and physical, to inform human-centered design. Traditional HF research normally focuses purely on human physical and cognitive abilities, making systems usable and safe. As such, HF tends to present facts and figures of the situation and user interactions with products, services, or systems. This is why we most often see the term in academia and highly regulated or high-risk fields such as healthcare, aviation, finance, and military. Due to the often more rigorous and in-depth testing needed for HF research, traditional HF researchers tend to be trained and educated in cognitive psychology, physical ergonomics or related fields. Many have advanced degrees, which is often a requirement for HF researchers.

Figure 2: HF Venn Diagram

Rather than siloed, the Human Factors field could be considered the broader term that includes UX (research and design), but also encompasses various disciplines such as Human-Computer Interaction, Ergonomics, Industrial Design and more.

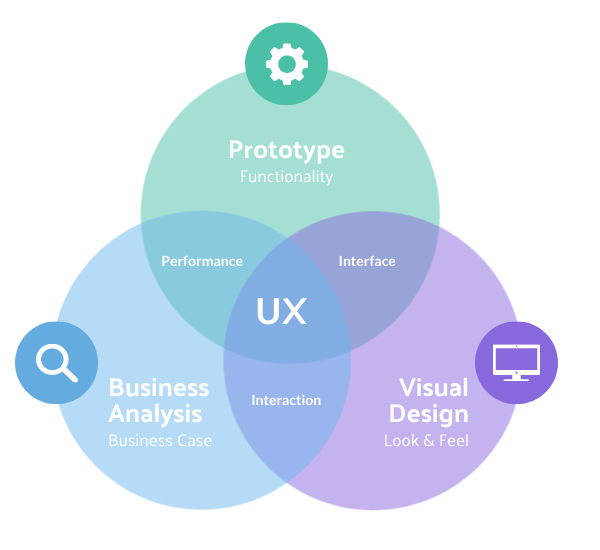

What is UX Research?

UX research is at the intersection of users’ needs, business needs, and constraints. Because it considers all of these factors, a case for UX can more easily be made in most industries. This is why demand for UX research can be found in fields like tech, ed-tech, finance, and many commercial B2B or B2C industries.

Figure 3: UX Venn Diagram

What does this all mean now and for the future?

This break-off of UX from traditional HF made sense at the time and is what made the widespread application of human-centered design possible. Through UX, sectors and industries that stand to benefit from some level of HF research were introduced to the concept and the benefits of human-centered design. These industries benefitted from UX research as they might not have from the introduction of traditional HF, as that would’ve been too burdensome, and not equally rewarding. As HF research is not always necessary, the rise of UX ultimately helped spread the parts of HF that were needed where they were needed without the complication of needing to know HF and needing to sell what is essentially a full scientific report to the “uninitiated.”

Now, however, the need for HF is growing and we can see HF is steadily being used in even the less regulated industries, places typically inhabited by UX research only. This can be seen from the increase in the job postings for Human Factors researchers/engineers in industries like tech and transportation. The increase in demand for HF research in these various industries can be attributed to advances in technology shifting how we interact with different technologies and the world.

In transportation, features like adaptive cruise control and the advent of self-driving cars changes the role of humans in vehicles. We can no longer simply rely on what we knew about how humans operate cars and the effects of distractions, etc. We need to understand the cognitive processes and mental models that go along with piloting/being in a self-driving vehicle; specifically things like human reflexes and predicting reactions under these new circumstances. In the tech industry, since virtual and augmented reality are such new technologies, you see a demand for HF researchers there to understand the ergonomics (physical and cognitive) of such systems and human capabilities and limitations surrounding these systems. As virtual and augmented reality gets adopted in various fields, like education and healthcare, we can expect to see a rise in demand for HF research in those fields as well. As illustrated by these examples, there is a need to adapt and develop new technologies to be human-centric, making the experience more enjoyable and safer. In general, advances in technology everywhere will lead to a rise in the need for HF researchers everywhere.